(China – 15 February, 2014) The expression, “digging a hole to China,” is a line every kid in America has heard before. Adults know the truth, but it’s a fun line to say to a child digging in a sandbox or similar. Jessica and I can both remember how this idea didn’t seem absurd to us at the time. “Wow! Is that true?” It certainly plays on a child’s imagination and lets them know… China is a place far, far away from home.

That sense of being very far from home lurked in our subconscious as we began our two weeks in China. As you will see it is a strange land indeed and not just very far from home geographically, but in almost every other respect.

Half-Price Books to the Rescue

When planning for China we only knew of two things we wanted to see/do: We wanted to see the Terracotta Warriors and walk on the Great Wall. Beyond that we were shrugging our shoulders and in clear need of direction. China is bigger than the US; how does one decide where to go and what to do during a two-week visit? Thank goodness I’d bought a China travel book while we were still in Austin.  Overall, the book turned out to be pretty lame because it lacked many important details when we needed them. What it was good for was providing a specific place-to-place travel plan after departing from Hong Kong: Yangshuo – Hangzhou – Shanghai – Xi’an – Beijing.

Overall, the book turned out to be pretty lame because it lacked many important details when we needed them. What it was good for was providing a specific place-to-place travel plan after departing from Hong Kong: Yangshuo – Hangzhou – Shanghai – Xi’an – Beijing.

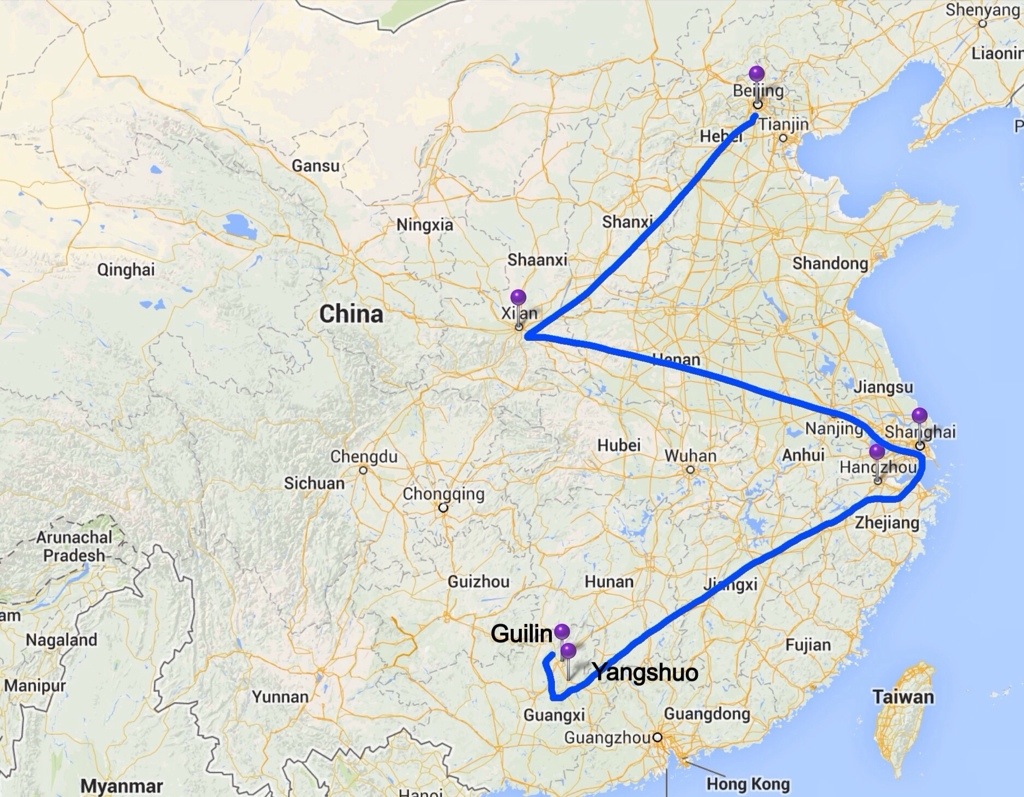

Most Americans have heard of Beijing and Shanghai, the two largest cities in China, but the names of the other cities we visited will be meaningless and puzzling to pronounce. That’s okay. Here’s a lightning-round primer just the same:

– Yangshuo is located in the southwest quadrant of China and boasts some of the most unusual terrain found anywhere on the planet.

– Hangzhou is a remarkably pretty city located closer to China’s eastern seaboard, not very far south of Shanghai, in the grand scheme of things. The centerpiece of Hangzhuo is a beautiful lake called Xi Nu (or West Lake). By all accounts the lake is the city’s heart and soul and they do a great job of treating it as such.

– Shanghai is not much more than a big city, but it’s uber-modern and so easy to like. Located on the east coast, Shanghai lays claim to having the busiest shipping port in the world. It also has great landmarks, museums, and, of course, shopping.

– Xi’an is one of China’s ancient capital cities and hugely important historically. Today it is most famous for being home to the Terracotta Warriors. To get to Xi’an we traveled back towards the west and a little northward about 14 hours by train.

– Beijing is China’s largest city (and its capital). While there is much to see and do in Beijing, our primary purpose for going was to see The Great Wall of China. Like Shanghai, Beijing is on the east coast and much further to the north.

If you followed all of the west-east-west-east directional zig-zagging, you’ll realize our route roughly drew an S-shape over China.

Strange Place, Yangshuo

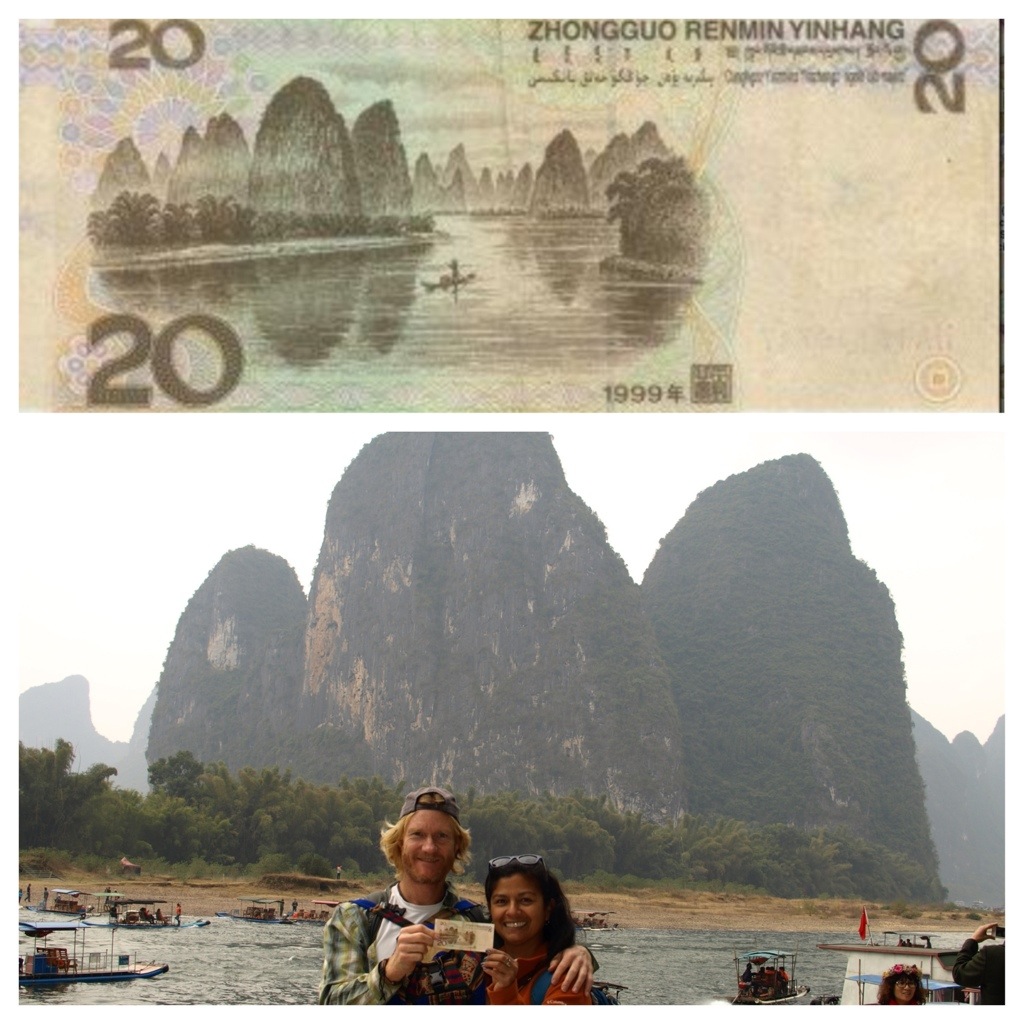

Strange and exotic may be the two best words to describe the landscape around Yangshuo. As we traveled around the area by boat and bus, I pondered how I would describe the uniquely shaped karst peaks in the blog. After much thought, I’m still not sure how to describe it. This is one place where a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

Getting to Yangshuo was a crazy, multi-step affair. We flew into Guilin (Gway-leen) from Hong Kong where we spent our inaugural night on the mainland. First impressions were spooky. The Guilin airport was on the outskirts of the city (just as many airports are with respect to the city they serve). When riding in the cab to the hostel we were treated to nice wide streets that were shockingly barren. We wondered, “Where are all the people?” Most of the buildings we drove past were all or half-finished, but in either case, uninhabited. Were we in the Twilight Zone?

By the time we entered the heart of Guilin, we found people and traffic and street vendors and more of what you’d expect from China.

Yangshuo Power Rafting

In the morning we took a shuttle bus from our hostel to the banks of the Li River where four-person motorized bamboo rafts awaited. Our guide for the trip to Yangshuo was Shau Nu. Thankfully for us he went by the super-easy nickname, “KFC.” A fast talker in both English and Chinese, it was fun to see KFC in action. He had folks laughing in two languages.

Oh noooo! Jessica accidentally left her iPhone on the bus!! She realized it right about the moment I snapped the pic below.

Jessica courageously put thoughts of losing her phone to the side and tried to enjoy the trip, but to claim it wasn’t a distraction would be a big fib. The feeling you get from losing something so vital can put a big ol’ knot in the gut, for sure.

Phone distractions aside, those bamboo boats sure created a racket. And there were hundreds of other tourists doing the same thing. Such an extraordinary landscape…turned into a go-kart track. It was an adventure, to be sure, but not very relaxing.

The bamboo boats end their trip at a spot made famous because its view appears on the 20 Yuan bill.

After plying the river, we were reunited with our bus and Jessica was able to find her phone. What a HUGE relief that was. We then rode the rest of the way into Yangshuo, where the bus dropped us off nowhere near our hotel. Um, okay. I guess we’ll ask somebody. And that’s when we learned that not too many people speak English in Yangshuo. Pointing and nodding eventually got us to where we needed to be.

Superbowl in China

When KFC had described Yangshuo, several times he said it was “very small.” I wonder if maybe very small doesn’t translate directly from Chinese into English. Yangshuo was no small town in our eyes… and plenty crowded to boot. Not so small that we couldn’t find a place showing the Super Bowl, neither. Yay!

An Australian ex-pat that owned a little restaurant showed the game through an Internet feed at 7:30 AM local time. Jessica and I were there. The Australian couldn’t care less about football, but he understood that it was a big deal to Americans and was happy to open his doors and serve us breakfast in front of a rigged-up screen. There were about 12 of us watching. All of the color commentary was in Chinese and the game was a lop-sided bust, but we were still quite happy to have been a part of it, especially while so far away.

In every one of our Yangshuo photos (and virtually ALL of our scenery photos in China), you will notice what looks like fog or morning mist. Unfortunately, it is neither. It is polluted air. Everyone that comes to China will inevitably talk about its pollution problem. Now we’ve experienced it first hand…and yes, it’s as bad as they say. There’s no way to overlook it. It’s literally in your face no matter which direction you turn your eyes (and nose). At no point did it ruin our visit to China, but it sure put a thick grey damper on every activity.

A day after our motorized rafting trip, we went on a second bamboo raft, this time we went old school (sans motor); so much more peaceful. I love this pic of all the bamboo rafts lined up and ready for tourists.

The very pretty Dragon Bridge.

Rain in Hangzhou

In general, we’ve had great luck with weather nearly our entire trip. But on occasion….we get snookered by less than ideal conditions. In pretty Hangzhou, it rained a bit. Never enough to keep us from venturing out to see the sites, but I do think it made us miss what might have been. I mean, if this place- West Lake -was great in the rain, how much more awesome would it be on a beautiful day?

One benefit of the rain was that it hid the air pollution really well. Is the sky gray because it’s raining or because the air is polluted? We chose to blame it on the rain.

Hangzhou’s West Lake is big enough so that visitors can enjoy a leisurely cruise across it. But not so large that the eye cannot pick out a towering pagoda on its opposite side. The entire circumference of the lake seems to be park, too. Kudos to Hangzhou for doing it up right.

Jessica and I rode bikes around part of the lake, took a turn in a pedal car, and explored it by foot. All good.

Sure, this photo is a little bit “staged,” but that really is us walking by the Hangzhou lake on a rainy day in February.

Specks of drizzle landed on the camera lens creating a cool “effect.”

The Hangzhou lake boats are finished like fine furniture. Look at this thing!

One more from around the lake…

Shanghai, High on Energy

The train ride to Shanghai from Hangzhou was remarkably short- only 1 1/2 hours on the bullet train. The arrival into Shanghai caught us totally by surprise. One moment we were cruising down the tracks at 300 kph and the next we were alone in the train with the stewards squawking at us in Chinese to get off. (At least I assume that’s what they were saying.)

Shanghai may not be geographically far from Hangzhou, but it is a world away in terms of character. We went from strolling around a peaceful lake in Hangzhou to weaving through a crowded pedestrian-only shopping district in the middle of Shanghai. People were everywhere. Departments stores and malls, everywhere. I swear there were malls packed within malls, like Russian dolls. On the street we were approached by vendors one after another. We’d gotten pretty good and softly shaking our heads and loudly saying, “Thank youuuuu,” yet one of them got through to me. I couldn’t stop myself from buying a pair of wheels that transformed my tennis shoes into wheelies. Anyone know how to turn a video 90 degrees?

Here’s an odd little incident to report. We were being photographed! And I don’t just mean by regular Chinese people, (which did happen a bunch). Twice we were photographed by men dressed in all black and carrying large, formidable-looking cameras at their hip. They weren’t raising their cameras to take pictures like normal people. They were clearly trying to do it on the sly. One of these two “men in black” passed very close to me. Jessica and I were walking down the street and looking at something to our right. I turned back to the front just in time to catch a glimpse of the (not so) secret agent rushing passed me on the left, camera aimed right towards us. Creeper!

Spot Jessica taking over the street.

Each leg of our China travels moved us further northward…into colder and colder climates. Shanghai was the coldest yet. Thank goodness we were prepared for it; three and four layers of clothing became a matter of routine. Our reward- SNOW! Real big fluffy snow, too. No, you don’t understand, we’re from Texas. We don’t see a lot of snow. Snow is something to smile and get excited about, and so we did.

Yuyuan Gardens in Shanghai.

Xi’an and Emperor Qin’s Underground Army

If you are familiar at all with the Terracotta Warriors, it is probably because you saw something about them on the History Channel or National Geographic. For the rest of you, here’s three sentences that will bring you up to speed. Around the year 200 bc, China had a supremely powerful (and crazy) emperor named Qin (pronounced quickly and sounding like, Chin). Fueled by self-importance, Emperor Qin ordered that his burial site be protected by a complete garrison of 8,000 full-size and life-like warriors. This army, complete with commanding officers, archers, infantrymen and even horses, was made piece by detailed piece out of terracotta clay, fitted with weapons, and then buried in covered pits, deep underground.

A tiny bit of background will help explain how Qin came up with his “brilliant” idea. In times further back than Qin’s, leaders were routinely buried with oodles of idols and trinkets, Qin simply took it to the next level. Going back a few more generations and archeologists and historians have discovered something much more chilling. In ancient times it was customary for an Emperor’s entire staff (generals, advisors, servants and, of course, his concubines) to be killed and buried along with their deceased leader. This practice was abandoned during times of war for practical reasons…because they couldn’t spare the manpower.

I had always heard that the warriors were “buried,” but couldn’t figure out what that meant. Were they put in the ground and covered with dirt? While this is mostly how they ended up, at the time they were buried they were placed standing (or kneeling in the case of the archers) in long and deep dugout pits. The pits were then topped with timbers that gave the warriors a roof over their heads. Above the timbers several layers of tightly woven mats were placed to keep out the dirt that was shoved back over the top of them….until the whole landscape was flat earth again. (Just like it never happened.)

As the centuries passed, earthquakes shook the warriors off their feet, breaking them like dropped clay pots. Time rotted away the wooden timbers that formed their protective roof, crushing them further and causing them to be truly buried. Only one warrior escaped the 2000 years unbroken. He is the magic archer.

All the rest that you’ve seen in photos have been found in pieces and painstakingly reassembled by archeologists.

In Person, Intense

Seeing the Terracotta Warriors with one’s own eyes is mentally/emotionally intense. I guess the enormous scale of the undertaking cannot be fully appreciated until you’ve stood on the edge of those deep pits and peered at the warrior’s faces. Contemplating what it must have been like for the individual laborers and artisans as they toiled away their lives for a lunatic Emperor is a natural place for the mind to venture.

Each warrior’s face is unique; most probably modeled after real people that lived at that time, though I’ve read that point is debated by the experts. One theory says every face was done in the likeness of the artist that created it. The last square shows one of the pits where archeologists continue to do their work…at night…after all the tourists are gone.

Some warriors are encased in glass for up-close viewing. Hundreds of the broken warriors remain down in the pits, waiting for their turn to stand again. All of the warriors were painted prior to being buried. Only traces of paint remain on a few of the warriors today.

Emperor Qin’s Army of the Terracotta Warriors was never supposed to be discovered. Nothing has been found in the written record (so far, at least) to indicate its existence. Supposedly, even the craftsmen that made the warriors were themselves killed to keep the secret safe for all time. And secret it was until 1974 when a local farmer and some helpers discovered the first pit while digging a water well. That farmer’s name is Yang Xinman, Since his discovery he has become a local celebrity of sorts. He even works part-time at one of the museum shops. And we shook his hand!

Xi’an Extracurricular Activities

It wasn’t all warriors all the time in Xi’an. Two other activities deserve mention. Xi’an’s city center is surrounded by its own ‘great wall,’ an imposing defensive barrier running 12 miles in a square that is nearly as impressive as the Great Wall itself. We saw every inch of it, too, on a rented tandem bike. Notice the smokestack spewing out pollution in the background.

Every night at 8:30, Xi’an puts on a major dancing fountain show at the base of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda.

Always clear what year it is.

Beijing’s Forbidden City

Chinese history is truly fascinating. And few places will give visitors to China such a visceral introduction to it like the Forbidden City. From our hotel it only took 25 minutes of brisk walking to reach it. It did require first entering the famous Tianamen Square, site of intense anti-government protests in 1984…that were soundly and bloodily crushed by the authorities while much of the world looked on. Security in and around the square was serious and plentiful. We even had to pass through a metal detector and have our backpack screened just to stroll through the square and look around. There’s not really that much to see; a couple of large monuments “to the laborers” of China and some large flower beds, but otherwise, it’s just a large open concrete space. Good for displays of military might, to be sure. A giant picture of Chairman Mao, leader of the communist revolution, hangs on the outside wall of the Forbidden City and overlooks the square. This also marks the place where he is buried.

At the northern edge of Tianamen Square lies the Imperial City (or Beijing’s “inner” city). It is surrounded by a thick, high protective wall. Within the Imperial City is an even smaller sub-section (still huge, by the way) called the Forbidden City. It too is surrounded by its own thick wall…plus a moat. (The Chinese sure were big on building walls!) The Forbidden City was so named because “commoners” were not allowed inside; the Emperor and his aristocracy only, please.

In walking around China, Jessica noticed how often the word forbidden was used for just about everything that was off limits. Signs might say, “Walking on Grass is Forbidden,” for example. It is probably a matter of translation, but we found their use of the word forbidden reached a comical extreme.

Great Tour Guide Has Bad Breath

Our exploration of the Forbidden City was greatly enhanced by Michael, the certified guide we enlisted to show us around. His English was solid, his knowledge of history superb, but his breath stunk like a sewer. It was very distracting. Offering him a mint occurred to me but couldn’t quite muster up the courage. What if I offered and he said, no thank you? Awkward.

The greatest thing about having a guide is being able to ask questions. Listening to an audio guide can be good and informational signs are better than nothing, but neither can compete with a knowledgable guide (bad breath or not) at making a tourist site come alive.

The chain of emperors recedes into history for thousands of years. We viewed the palace buildings where they held council, the thrones where they delivered decrees, both devastating and benign, and the living quarters where they changed their underwear. We even learned of one Emperor who was almost certainly gay and another that (according to the official royal documentarian) once “got busy” with 87 concubines in one night. That emperor died at 32, by the way.

It was a game of thrones for these emperors, as different thrones- centered in different buildings -were utilized depending on the occasion. Above each throne are Chinese symbols that convey philosophies intended to guide the emperors in their rule. One of them says (something like), “Do little to achieve much,” a reminder for the emperor to rule with restraint.

The Great Wall(s) of China

The great advantage of visiting a place- like the Great Wall -in person is that you not only get wowed by the sheer spectacle of its magnificence, you are more inclined to learn new things about it. First off, we that learned a widely believed ‘fact’ about the Great Wall is actually not true at all: the Great Wall cannot be seen from space with the naked eye. Myth-busted! We learned the Great Wall of China that everybody knows and loves is only one of several walls built by the Chinese over the past 3,000 years. The first walls were built in the 8th and 7th centuries bc out of clay and dirt. Today those earliest walls have deteriorated to the point where many sections are visible only to the trained eye of archeologists. Some walls were built in one century and then disassembled and rebuilt elsewhere in subsequent centuries. It’s a fascinating history and so much more disjointed than I’d previously understood.

Anyone visiting today’s nearly 5,000 mile long Great Wall has many wall ‘locations’ to choose from. Badaling is the name of the site where most tourists go; it’s nearest to Beijing and refurbished to a stunning state, perhaps looking better now than it ever did in the past. The knock on the Badaling section is that it is too crowded and too touristy. Wanting a more peaceful experience, Jessica and I went to a section called Mutianyu– located about 70 km (43 miles) northeast of Beijing. This stretch of the wall was originally built in the 6th century, and then rebuilt about a thousand years later (during the Ming Dynasty). Ming’s crews rebuilt it to a very high standard and Mutainyu remains the best-preserved expanse of the Great Wall today.

Walking the wall is a calf-killer. Because the wall follows the contour of the rolling hills, there are steep ups and downs. Photos so often fail to convey elevation and depth so I’ll just tell you….the pic below finds Jessica making her final assault on an extremely steep set of steps.

We enjoyed being on the wall in relative seclusion.

The toboggan ride down from the Great Wall was conceptually incongruent, but oh so much fun.

This was an enormous post (because China is an enormous country). If you seriously read through it all, my hat is coming off for you.

When Jessica and I initially presented (to each other) the list of countries we would most like to visit while traveling around the world, neither of us included China. It was too far, too foreign, and too scary. However, in the end we concluded that traveling the world for a year and NOT going to China would be tantamount to negligence. And so we took the plunge.

Our visit to five points on the China map (counting Guilin and Yangshuo as one) gave us a solid overview of China. We are so glad for the experience, too. In some small way, being there was fulfilling the childhood fantasy of what it would be like to dig through the Earth and catch a glimpse of Chinese life.